When the pandemic turned millions of employees into remote workers overnight, it accelerated acceptance of a technology-enabled distributed workforce that had been gaining speed for years.

The lasting effects of this technological change—and the next digital disruptors in the workplace—are among the topics on tap for the newly created Humans in the Digital Economy Lab. Part of Columbia Business School’s Digital Future Initiative, the lab is led by Stephan Meier, the James P. Gorman Professor of Business.

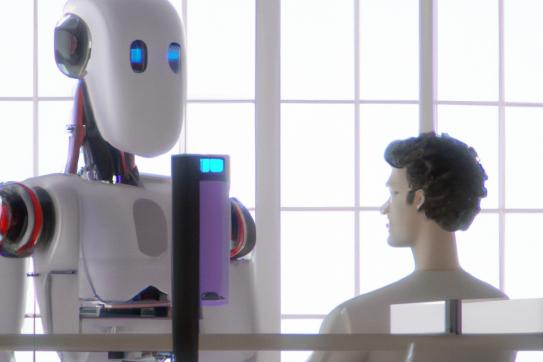

Bringing together experts from interdisciplinary fields, the lab will investigate how technology and digitalization affect and interact with people in organizations. Projects will focus on elements of work including automation across industries, the composition of the workforce, and how the workplace could be reimagined.

For Meier, the rapid adoption of technology presents ample new research topics. Some of the questions he intends to explore include:

- To what extent are machines capable of replicating work currently done by humans?

- What is the current nature of the interaction between humans and machines, and what should it be?

- Under what circumstances do they work better together, in partnership, rather than having a machine displace a person?

As one example, Meier’s class, Future of Work: Strategy & Leadership, takes an in-depth look at the interactions and partnerships between computers and humans in Morgan Stanley’s wealth management division. The case study examines how the role of financial advisor has changed over time.

In the past, an advisor would evaluate a client’s risk appetite and develop personalized investing recommendations. Now, Meier says, robo-advisors can generate investment strategies aligned to people’s preferences, giving them the confidence to take control of their own finances. In response, the advisor’s role has shifted from relying on computers that create custom plans for clients to relationship building and providing service.

“In the human-machine interaction, the humans are very important, but they’re doing different jobs than they did before,” Meier says. “Whatever needs trust or empathy, a machine is not as good at that, at least not yet. Those conversations, those human interactions, remain very important.”

How to prepare for these changing roles will be another important focus for the lab, as will the new skills that people will need to work effectively alongside algorithms, artificial intelligence, and the new technologies still to emerge.

Even if a job remains untouched by automation, doing that job remotely has enormous implications for workers, employers, and basic societal structures.

Millions of square feet of office space still sit empty three years after the start of the pandemic. Meier and others at the lab will explore how this simple geographic shift will continue to transform the economic landscape. In February, the lab hosted a panel discussion looking at changes in the workplace and their effects on the real estate market. Experts from academia, industry, and government discussed declining commercial real estate values and how cities can cope with the resulting tax revenue shortfalls.

For employees, remote work offers numerous advantages: time and money saved by not commuting, better flexibility with childcare, and fewer disability-related employment obstacles. And members of groups impacted by negative bias and discrimination in the workplace may prefer to work remotely. But Meier points out there are many questions still to be answered in this distributed workforce model.

“How do you make a career when you’re not in the office? How do you network? How do you negotiate wages over Zoom?” Meier says. “For our students, there’s hopefully some very practical career advice that will come from all the people involved with the lab.”

Overall, Meier remains optimistic about the future of work life and says he’s excited by the opportunity the lab presents to help navigate the very real human challenges ahead.

“With our Digital Future Initiative, we’re talking about new technology,” he says. “My lab focuses on how that interacts with a very, very old technology: the human brain.”